Heartworm disease, caused by a filarial nematode (Dirofilaria immitis) is an increasingly serious animal health problem for dogs in Hungary. This mosquito-borne disease can cause serious conditions if left untreated, and its incidence has clearly increased in recent years.

The summer period – especially during dog walks and hikes – carries an increased risk, as mosquitoes are most active at this time of the year. That is why it is important for owners to keep their dogs on preventive medication, which significantly reduces the chance of developing the infection. Early signs of heartworm disease may include fatigue, coughing or general weakness – it is recommended to consult a veterinarian as soon as possible if these are noticed.

The aim of our research was to better understand where and how frequent heartworm disease occurs, and what factors may increase the risk of infection. We used two approaches to do this: first, we molecularly examined mosquito specimens, and second, we built on the dog owners’ own experiences using an online questionnaire.

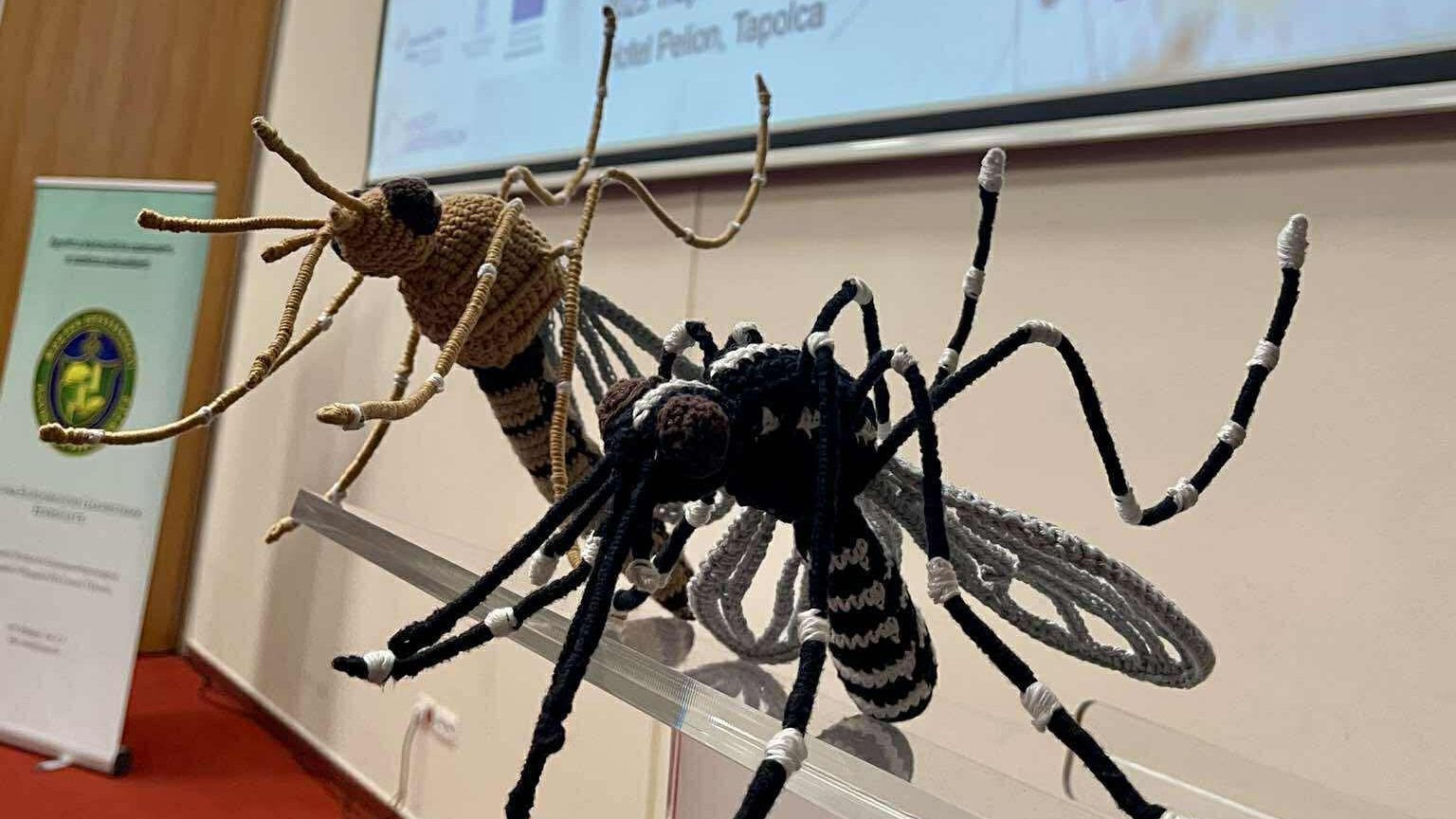

The latter provided particularly valuable information: we received data on approximately1600 dogs from all parts of the country. Based on the responses, the infection rate is highest in the southeastern (47.8%) and eastern (43.4%) regions. In the case of older dogs and dogs kept mainly outdoors the infection is much more common, presumably due to longer and more frequent exposure to mosquitoes. In the mosquito samples, the parasite was also found in invasive species, such as the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) and the Korean mosquito (Aedes koreicus), but the native and common inland floodwater mosquito (Aedes vexans) was also often infected. The spread of invasive mosquito species can be tracked on our Mosquito Monitor website.

Our results clearly demonstrate the key role that dog owners play in gaining a more accurate picture of the spread of heartworm disease in Hungary. Through such citizen science-based questionnaire surveys, we can also collect data from areas, where collecting and examining mosquitoes is not available or is time- and cost-consuming – so the feedback from owners is an irreplaceable tool for prevention and control. Our colleagues have also issued a more detailed scientific paper examining such benefits of community science.

We would like to express our gratitude to all dog owners who filled out the questionnaire, as well as to the Bogáncs Pet Shelter in Esztergom, the Rex Kutyaotthon Foundation in Budapest and Net Vet Kft. in Debrecen, who supported our work with additional data and valuable advice during the survey. Special thanks to András Tóth and the Qubit editorial team for reporting on our preliminary results and encouraging readers to participate in the research.